It’s been a long few weeks–I’m traveling back and forth for lectures, office visits and events and find myself staring out the plane window more often than not. This morning, on the plane ride across the country from San Francisco to Philadelphia, I remembered that this weekend is also a big weekend in college swimming. I couldn’t help but remember my days in Ohio as I crossed over the state, high above hovering around 30,000 feet. The upside of being on a plane so much is that I’m left with my own thoughts, internet-free (mostly), able to write for as long as I can stay awake or until the battery on my computer runs out. Today, a huge rally cry for my teammates past and present, and the current National Championships in swimming. While I talk about swimming a lot, this is about more than swimming: this is about the fact that you only get so many chances in life, so take them. Use them well. Once they’re gone, you don’t get to go back.

Swimming: The love of competition.

Alumni meet, Fall 2010.

I sat on the bleachers of our rickety old Natatorium, hard concrete rows crammed into the upper edge of the 1925 Gregory Pool. A handful of us arrived early that Saturday morning, watching the young swimmers practice. Outside, the early morning chill of a brisk fall permeated the small college campus. Inside, the smell of chlorine echoed off the linoleum walls, stinging my eyes and nostrils in an all-too familiar way. All-American plaques lined the hallways, stacked in tens, wrapping around the pool deck, an homage to all the great swimmers of our colleges’ past.

Parents and alumni trickled in, coffee in hand, watching. The upper bleachers were poorly lit. Shouts and whistles from practice reverberated in the room; the sounds of thirty-six hands splashing rhythmically slapped back and forth against the water.

My body tensed in my abs, stretched in the shoulders, my fingers itching to extend and pull the water again, even after too many years gone by. The memory of being a swimmer sticks in your blood, in your muscles, despite the aging weariness of work. I could feel the past, knowing that years ago, I wasn’t sitting here; I was there. There was a time when it was me that was walking, feet cold against the tile floor, bare and ready, suit straps taught against my thighs, limbering up, a sea of bodies intermingling behind the diving boards, waiting for the cue to start. Tired, exhausted, exhilarated. Ready to perform. Every single day.

Back then, we were an army of swimmers, a mess of bodies in motion, a collective bigger than an individual, a set of minds that worked interchangeably. We didn’t necessarily all like each other all the time—and so goes the social peculiarities of teams, groups, and people—these dynamics magnified as seniors and freshmen battled it out on the lateral playing field.

Outside of the pool I was awkward. I was gangly, shy, strange, insecure, a mess of emotions and flighty hands, unable to string words together in sentences. The men were men, or boys; the women also alternating between mature women and ridiculous girls: all of us were, for the most part, naked and hormonal and tired and hungry. Half the time someone in lane two was dating someone in lane six. You could usually tell by which girls still bothered to put make up on before practice.

Yet in the pool, in the water, cold streaming past your face, each gasp of breath taken and flip-turn turned, you weren’t a mess of social norms. You were just you: you and yourself, your brain, your competition, your ability. The pool was freezing; every day the bitter bite of the water hit my face, the routine of lining up and jumping in with the sweep of the second hand ‘round the clock, indicating our instructions, our commands. Beep. Go.

That’s the old pool! My life for four years; it’s being torn down and a new, larger pool is going up.

And we moved, we jumped, we jostled, we argued for place in the lane, silently, fingers grabbing toes and passing one another if the timing wasn’t right; I wrestled against someone slower than me, someone insistent that I take the spot, someone who wanted me to be third. Weeks later I would gravitate towards leading the lane; towards pulling the tide, towards starting the drafting sequences. I would battle with the boys, egos on line, competition fierce. Some days I’d spend two hours side by side in a drawn out test of strength that lasted over hundreds of laps. Our fingers would sting at the end, our egos possibly bruised by the fierceness of wanting to win, but our spirits championing the fact that neither one of us gave in, neither one of us caved.

And we would battle good-naturedly with each other, knowing that this micro-competition would prep us for invisible competitors training is faraway pools; for purple suits and brazen stories of our true adversaries getting ready for the challenge.

Looking down at the swimmers moving rhythmically back and forth in well-spaces sequences, I marveled at the physicality of it all: the bodies were gorgeous; their sleek physiques and lean torsos glistening water droplets across their chiseled bodies. Swimmer’s hair shines like a Greek goddess; these muscular animals galloping across the surface without seeming to have a care in the world. The best of them have a singular focus on their mind, day in, day out: to perform; to win. To achieve. The definition of success is marked; the ideas concrete, the measurement the clearest feedback you might ever get in your life.

And so they engage, patterns and hierarchies emerging, testosterone raging and hormones drumming, the ultimate test of performance shining from the lights of a red-numbered display:

Lane 4: 1st Place, 51.09.

To perform. To be the best. Singularly.

Will the hard work be worth it?

It’s not sugar-coated, it’s not magic, it’s certainly not easy. Memory tricks us, at times, into painting it as a picture of glory days, of facility over time. We forget the pain of exertion the farther we are from it, and our minds weight unequally the glory of achievement in memory reconstructions. Yet etched in my mind are also the times spent tearfully worrying behind the closed doors of the coaches offices—of the panic ripping through my body each time I had to anchor a relay, of my insecurities and weaknesses, both physical and mental. Adding pressure to the task was the mounting challenge that it seemed I would never be able to accomplish: to focus on both academics and swimming, and do both successfully. I have notebooks lined with illegible scribbling as I fell asleep in class after class. I was worked. It was hard, in the truest sense of the word.

Sometimes we forget what the brain thinks in that moment, the worry painted across my forehead, the thoughts that consumed me: Will I be able to perform? Will what I do matter? Will I be fast enough? Will I be successful?

Will the hard work be worth it?

And you can’t know, because you’re not there yet. Some people will fall to mental struggles; other people will have physical ailments; some won’t be capable of imagining what they look like when they break every record possible; when they burst through their limitations; when they escape the chains holding them back and dare to dream, to perform, and to enjoy the process.

Rare moments of beautiful performance dance across my mind; personal achievements that still startle me to this day. Moments spent flyingthrough the water, hands curved in perfect precision, energy and effort coordinated in a seamless release, a mental precision uncatchable.

Sometimes, unbeknownst to even me, I would break into the surface of the water, glide forward, and watch in astonishment as my body danced and darted forward, laughing, skipping, bursting through the waves and dropping seconds off of all of my times. To limit what I was capable of to the beliefs in my brain was silly. I could do far more than I knew.

This is all you get.

And at the Alumni meet, my hands are folded across my lap, my comparatively lethargic 28-year-old self catching hold of the memory of my former collegiate days, my fleshy feet padding across the surface, the years patterned in my brain as episodic memories. I re-fashion those endless four years in emotions and standout moments, and I can see my freshman self, teary and weary, climb out of the slow lane, move towards the middle lane, challenge the senior lane, and move upwards; I can see when we welcomed in new crops of talent each year, when I began winning events for the first time, how all of us built our bodies from a weakling to a structured, strong upper physique.

I cannot thank swimming enough for changing me into the person I am today; for the endless iterations testing my mental and physical prowess; for carving out of all of the possibilities of who I could be to become something absolutely great. In the short time I spent at school, I finally felt like I became someone, something, and then, before I could really match my mind to reality, my school pushed me out the door, depositing me on the doorstep of a new city with a piece of paper and not much more than a set of memories.

On the bleachers, sitting, jeans pinching my belly, soft thighs no longer brusquely shaped to perfect; I am not there anymore. I am no longer a college student—even though once, I was. It was; but I am no longer a part of it. My body, the cells, the pieces, the fragments; it was as if the water within each small cell leaned forward, thirsty for synchronicity with the pool’s rhythms, and I could feel the tingle in every inch of my muscle fibers, longing to jump in.

You’re all done; that’s all you get. Goodbye.

I return almost every year, sweeping my eyes across the campus trees, noting the huddled buildings tucked along the hillside, watching students stream in and out of the classrooms giggling. Notebooks tucked underarm, the clock bell chiming each hour, denoting the river-like passage of time; always moving; never staying still.

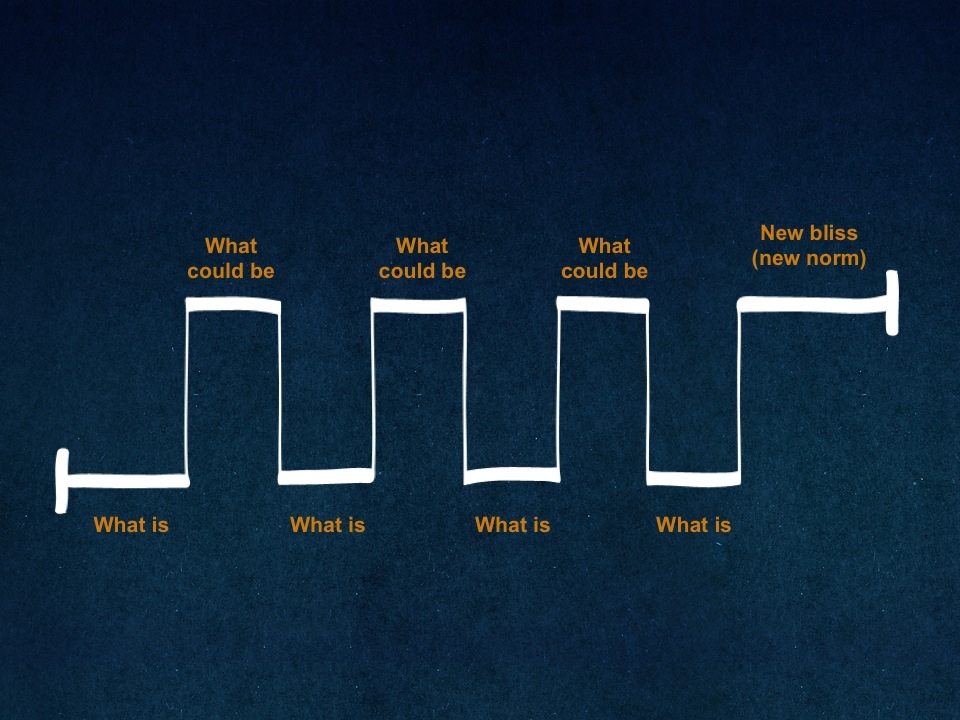

Everything changes. We hold onto a strange idea that life is fixed and permanent; that what happens today will be similar to what happens tomorrow, or a year from tomorrow. In reality our selves change every few years. Life is a constant re-invention; in the pool, each swim is a chance to do what you’ve already done or carve out a new print in your abilities by shaving seconds off of each performance.

The bodies in front of me, below, beneath the bleachers: they don’t know the shape of the future, of life after college, all you know is what you currently have. Jobs and families and careers are vague, fuzzy shapes. More pressing on the psyche for them is the feelings of the day, of the moment: They think, today I am tired. Today, my muscles ache from double practices. Today, I’m mentally and physically fatigued, worn out from hurling medicine balls across the tennis courts at 5 in the morning, from racing against the machine with the ominous swim benches, from stepping up to do test set after test set as the coaches glare angrily down at my inability to perform.

But you have a chance.

I cannot go back, except in my mind.

You’re still on the other side of the future. You have the possibility, the opportunity, the chance.

Will you take it?

While there, I know what it feels like: it feels like eternity. When you leave, it’s over. You don’t get to go back.

Last year, at the close of the 2011 championship, I watched as the men’s 400-free relay team captured the national title by half of a point, snatching victory from the ever-ominous rival team. I stared at the computer screen, refreshing the live-stream over and over, watching the commentary from all of my current and former teammates rapidly pop up on the screen. In those moments, I catch a glimmer and my heart races and pounds and aches, because I know what it’s like to be a swimmer. I know what it’s like to be there.

This weekend, swimmers from all over the world collect to match up in the great performance show-down of the nation. While no rival for March Madness or the media buzz of the Olympics, these events are still special, wonderful, spectacular.

You don’t get these moments back again – you live them once.

You have once chance.

And then my mind turns sharply from the linked associations and neuron firings pulling me deep into the memories of a time when I almost conquered the pool, when I dared to dream larger than myself and let my body take over, when I faced my coaches and teammates and said Yes, yes, I will do this. I will take this challenge.

Slowly, my mind unravels the history of the pool and I’m back in the sweaty chlorine of the upper bleachers of the old pool. I shake loose the memories and look forward to the possibilities for tomorrow, seeing the pavement of an uncharted idea rolling out under my footsteps, as though each foot prints a mark on hot asphalt, leaving a track and trace.

Do not let it go by without giving it every inch of what you’ve got.

You only get this chance. Let go of the fear. Of the uncertainty. Of the demons. Of the doubts. You’re the best you ever will be, and you’re more capable than you’ll ever know.

Good luck, Big Red.

You all mean the world to me.